Initials B.R.

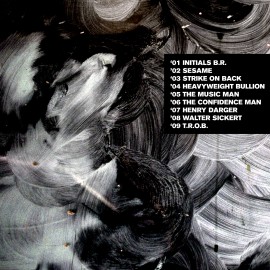

’01. INITIALS B.R. we have seen the moment of our greatness flicker

’02. SESAME we never sleep

‘03. STRIKE ON BACK we play with fire

‘04. HEAVYWEIGHT BULLION we buy gold

‘05. THE MUSIC MAN we are open for business

‘06. THE CONFIDENCE MAN we give you our word

‘07. HENRY DARGER we need a moment alone

‘08. WALTER SICKERT we have got to be kidding

‘09. T.R.O.B. we quit

BONUS TRACKS:

INITIALS B.R. (Single Edit)

SESAME (Single Edit)

THE MUSIC MAN (Single Edit)

THE CONFIDENCE MAN (Single Edit)

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

PRELUDE TO INITIALS B.R.

The first record I was ever given—or ever really owned for that matter—was LL Cool J’s Bigger And Deffer. When I received the present for my eighth birthday from my father’s coworker, I had no idea what was in store for me. It wasn’t Elvis (my first musical infatuation). It wasn’t David Bowie (my perennial musical hero). But it was utterly new. And it was mine. It clearly left an impression…

I don’t claim any kind of authority in the realm of rap knowledge. But like anyone concerned with some subject over a long period of time, you discover at some point that the individual present moments that seemed so dire at the time have congealed into a historical perspective that’s far more meaningful. Everything lines up in rows and columns and reads like a story. With regard to my rap romance, I can evaluate the world I lived in at any given time in conjunction with the music to which I listened.

For the most part, through my listening childhood, I was still just a kid. I chose Public Enemy and Ice Cube alongside Moni Love and Father MC. It was a strange, enchanting world that I was young enough to ingest, but fresh enough not to process. I noticed things change in my relationship with rap in the early and mid-nineties, as grunge and alternative began to hack at the music industry and the subversive urban genre grew into its hand-me-downs. Wu-Tang Clan, The Notorious B.I.G., Nas, A Tribe Called Quest: these figures heralded a new age for a new musical landscape. I went through puberty with this music, growing with it as it too began to demand the respect of adults. And by the time I finished growing twelve inches in eighteen months, I felt so intimately involved with rap music that it was more familiar to me than my awkward body. I had arrived and so had rap. I drove my car around Denver consumed, blasting the opposing epiphanies of Common’s Resurrection and Company Flow’s Funcrusher Plus, marinating in the defining spectrum of my musical understanding, thinking without worry, “It will never get better than this.” In some ways, for me at least, it didn’t.

In 1996, when Busta Rhymes rapped “There’s only five years left” in the introductory track of The Coming, he wasn’t far off. As the nineties elapsed, the schism between commercial and underground rap became the defining characteristic of the genre itself. Entrenched against Puff Daddy’s & Hype Williams’s decadent and blinding vision of the promised land, the indie renaissance made Rawkus Records the Mecca of underground hip-hop culture. Yet just as soon as it had risen to prominence, it pulled its best Sugarhill Records impression, short-sightedly letting their greed get the better of the music they built. Soundbombing II was the zenith pronouncing the denoument of golden era rap, bearing “1-9-9-9” as its poster-child and Mos Def & Talib Kweli as its prophets, bragging that they knew the real Eminem as he shrewdly slipped away towards unbelievable fame and fortune. The abysmal self-destruction of the Rawkus enterprise was the Y2K of rap. By 2001, the upstarts were doomed. It took just five years.

In the post-apocalyptic rap world, New York crumbled at the hands of the marauding South, the West built their Alamo around the great white hope and gangster nostalgia, and avant-gardists such as Def Jux and Anticon scurried through the rubble surprising the establishment with firefights like erratic survivalist militias and pesky terrorists. Meanwhile, against all odds, the music managed to conquer the world. But we all know how that went: Jay-Z the emperor, Kanye the crowned prince, 50 Cent the enforcer, Lil’ Wayne the court jester, Drake the savior, and more nobodies than ever fighting for the crumbs. Here we are.

But really, where are we?

People don’t rap years anymore. “2006″ doesn’t sound cool. We’ve arrived in the future and been here for a decade. Somehow, this millenium still feels alien. I wouldn’t say I’m simply nostalgic. It’s something about the gestalt of the decade—it doesn’t congeal.

As cliché as it has been to revisit the deaths of Christopher Wallace and Tupac Shakur and to aggrandize their talent, the transition into 21st-Century rap music has eerily reflected the fate of their ghost-voiced posthumous catalogues. After two decades as a fearsome outcast, rap music, the enemy of American Puritanism has ascended into its own life-after-death and been rewarded for all its earthly effort with everything one could imagine. The popularity of urban culture, the modernity of the genre itself, and the investment of major-label record companies in rap markets has turned the art form into the number one selling genre in all of music. Furthermore, the mixtape and DJ culture it created became one of the most successful translations from physical to digital media delivery, playing a pivotal role in the redefinition of the material of recorded music. Without a doubt, in the last ten years, we’ve seen incredible success and we’ve heard incredible music. But we’ve also come to know something about authenticity.

Take it back to ’88 (one of the best sounding years you could ever speak). In that year, Rick Rubin left Def Jam because of conflicts over musical integrity, upset that rap music was becoming more concerned with commerce than with creating moving art. It was a hint at what was to inspire the late-90s conflict between underground credibility and commercial success. Just a few years later the war bore the two sides their prophets. In ’94 (“rugged raw, kicking down your goddamned door”), we received two of the best rap albums ever by two of the greatest rappers to ever pick up a microphone: Notorious B.I.G.’s Ready to Die and Nas’s Illmatic. The former exploded with critical acclaim into an international phenomena; the latter received the first 5-mic review in The Source and sold disappointingly. But what the character of these two albums embodied, what the tenor of these two voices conveyed, was a deep dichotomy of artistic expression.

When an artist creates his work, he stands in himself to engage what he is and what he knows. When an artist sells his work, he goes into the world to engage what it is and what it wants. All artists operate on this spectrum, moving between persona and position, between actor and individual. In 1994, what B.I.G. and Nas established for the rap world were the definitions of public music and private music. B.I.G. raps on the corner, for the corner; Nas raps from the corner, transcending the corner. B.I.G. raps in a mansion, in a Benz, in a fantasy; Nas raps at a barbecue, in a bedroom, on a pad. Where is B.I.G.? “The back of the club, sipping Moet is where you find me. / The back of the club, macking hos, my crew behind me.” Where is Nas? “I be ghost from my projects / Take my pen and pad for the weekend, hitting Ls while I’m sleeping. / A two-day stay, you may say, I needed time alone / To relax my dome, no phone, left the nine at home.” It took me years to understand what these albums were, but when I did, everything clicked.

The 2000s, for me, have been about finding private music, however publicly it may be distributed, against an overwhelming inundation of public music, about searching for honesty, however it may manifest, against a tsunami of rap factory product. It’s been about trying to breathe in a dump of bloated mixtapes and turgid recyclables, hoping to come across something that might remotely resemble the Illmatic architecture that eschewed a jam-packed buffet for the craft of nine perfect songs.

Since 2000, for as long as I have been making rap music, it has been all done up in heavenly gowns, shrouded in celestial mists, reeling, opiated, Roman. Initials B.R. is an elegy of the 90s as much as it is an ode to the 00s. It is a glance back at the days when we rapped our years like mile markers on the road of history. It is a hymn to the vastness of possibility which in the 21st Century forgets what year it is except that it is the future.

Initials B.R. is my attempt to cover the public/private dichotomy in narrative form, each song being a stage in the journey of, on the one hand, making an album, and, on the other hand, forging and forgiving a career. We compose. We practice. We share. We present. We perform. We sell. We work and we tire. And when we have exerted our effort completely, we concede to fate. We finish; we put our things in order; we quit. Initials B.R. is my attempt to come to terms with being impelled to make art, with selling my work on stage and in stores, with lying to listeners, with self-delusion and make believe. It is as inspired by Company Flow’s Funcrusher Plus and Common’s Resurrection as it is Baudelaire’s “Le Cygne” and Eliot’s “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” It is an homage to con films and musicals. It is my own silly Makaveli legend.

But most of all, it is done. I hope you enjoy.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

This album was made in Cambridge, MA and Santa Fe, NM from 2005-2008 and mastered by Alan Douches at West West Side Music. The photograph for the cover art was taken by the very talented peon. This album would not exist without its initial conception with B.R.other Stephen Brackett (!) aka Brer Rabbit. It’s been a long time coming and many thanks go to Mom and Dad, my wife Caroline, Molly and Robert, Joey and Alana, Thom, Farhad, Devin, Torin, Galen, Sam, Simone, and Big Digits for their influence and support during the making and releasing of the record.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

PRESS

Ever wanna kick yourself for not getting hip to an artist earlier because it is just TOO badass for your noodle to comprehend? Well, that was me recently when I came across Masshole extraordinaire Luke Kirkland‘s too-big-for-the-boombox hip-hop project INITIALS B.R. and all the ruckus it was raising. Also a member of Depression-era indie ballers MARCONI and post-punk reverb idols NIGHT RALLY, Kirkland comes out of the gate with synth pad swooshes and a chopped-up drum sample with some serious groove muscle. Definitely not what I was expecting, but holy moley this one is a keeper. Songs like “Strike On Back” from his most recent album Initials B.R., released in April of 2011, are swing-heavy and have been known to make even the most hardened pit veterans shake their asses like it’s 1994. Mistah Kirkland produces the beats himself from a massive catalog of old-school soul, funk and roots-rock treats, propelling them with huge and distorted drum tracks that lazily snap and lock into place to get those hips twisting and feet flopping — breakdance bandits will rejoice in Kirkland’s undeniable dance-floor wizardry. Luke ain’t a half-bad rhyme spitter either, and an unwieldy collage of vocal samples backs him up. Unfortunately he has not scheduled any upcoming shows as of today, but rest assured that he will be back, and you already know the Hass is the place to find out when. In the meantime snap up his back catalog and soak in the crunk of his backbeat electroni-hop like sweet lotion for your groovy flesh!

—The Boston Hassle